Winter in the Trenches 1914-15

Civilians to Soldiers

'The Superficial and the Essential' Autumn 1914

Liverpool Scottish Tumbridge Wells 1914

The Liverpool Scottish arrived in France at the beginning of November 1914, one of the first infantry battalions of the Territorial Force to join the British Expeditionary Force. They arrived in the period almost immediately after the 'Old Contemptibles' of Regular Army (a 'contemptible little army' according to the German Kaiser Wilhelm) had fought alongside the French and the Belgians in a highly mobile campaign with a retreat from Mons to a sharp blocking battle at Le Cateau and beyond to a phase of checking and throwing back the German advance on the River Marne. This was followed by the "Race to the sea" as both sides attempted to out flank each other to the north. This estabished the trench line that ran 400 miles from Nieuwpoort on the Belgiun coast to the Swiss border. By November 1914, the Regular Army had suffered many casualties and the battle had settled into the pattern of trench warfare that was to persist for most the next four years. The Scottish moved into the trenches on 27th November at Kemmel, about six miles south-west of Ypres (Ieper). The trench system at that stage was very haphazard and not the highly structured system of , say, 1916. There was no depth, no continuity, no communication trenches, no drainage and no sanitation. The Liverpool Scottish underwent a transformation from peacetime civilians to wartime soldiers. Part of that transformation was learning what was superficial and what was essential in warfare. On November 27th 1914 the battalion was 26 officers and 829 other ranks and six weeks later mustered only a total strength of 370 men: the causulties being mainly to the winter conditions rather than the enemy.

The Liverpool Scottish came into the 3rd Division of II Corps (a Regular Army formation) and was initially addressed by the Corps Commander, General Sir H. Smith Dorrien, to the effect that, with the co-operation of the Russians, the war would be over by the summer of 1915. The Regimental Historian records that newly-arrived citizen soldiers of The Scottish 'were surprised to learn that the Staff expected the war to last so long'.

The Liverpool Scottish went into the trenches for the first time on 27th November 1914. The Regular Army would have been very concerned about an unknown battalion of part-time Territorial soldiers with no experience of warfare joining them. At home in the United Kingdom, the Secretary of State for War, the famous Lord Kitchener, preferred to raise a whole new army from scratch rather than rely on the Territorial Force which he considered to be of very variable quality. This would in fact become known as 'The New Army' and would be tried in the Battle of the Somme in 1916, but not before the Territorials had proved themselves.

The British Army 1914

The original contingent of soldiers sent to France to oppose the German invasion of Belgium in August 1914 was called the British experditionary Forece or B.E.F. It intitally consisted of soldiers of the Regular (full time) Army, they are often referred to as Regulars. By November 1914 they had suffered considrible loses in at least two months hard fighting. The only possible source for replecements, at least in the short trem was the Territorial Force. Made up of civilians with an ordinary day job but who did military training at weekends. Today, they are known as the Territorial Army and still serve in places such as Afghanistan.

The infantry Infantry of the British aremy was made up of companies which at full strength were about 225 infantry soldiers (the Army in 1914 had just gone from smaller companies of about 100 to 'double-companies' of about 225. There were four of these larger companies to a battalion. A Battalion therefore was about 1000 infantry soldiers (1914), commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel.

These battalions were grouped together in a brigade. In the infantry of 1914, a brigade was normally four battalions with the support of guns from the Royal Field Artillery. The Royal Artillery was also organised into"brigades" but these were smaller than infantry brigades.

The Liverpool Scottish entered the front line at the end of November 1914, with 855 soldiers. By the end of January 1915 following terrible winter weather the total strength had fallen to 370. Almost all of the decrease was caused by men falling sick; in that period there were only about 30 killed or wounded. When the first draft of reinforcements arrived from England, they virtually doubled the active strength of the battalion.

The Liverpool Scottish prepare for the Trenches in Belgium

The Pre-War Adjutant

The Pre-War Adjutant

The first 'superficial' casulty was the sword. The previous adjutant of the Liverpool Scottish, Captain the Hon. AH Maitland of the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders, is shown here (probably in 1912). He is wearing tartan breeches (apparently in Forbes tartan) and riding boots. He is carrying a broadsword with the half basket hilt used by field officers (majors and above) as well as the Adjutant. He seems to be dressed for field service as the strap for what is probably a haversack is below the cross-strap of his Sam Browne sword belt.

Despite serving in an infantry battalion Adjutants are mounted officers as they rode a horse and wore spurs. Captain Maitland's spurs can just be seen at his right heel . This tradition is maintained even today as the Army's No 1 Dress (a ceremonial form of uniform) and Mess(evening) dress when those officers (including adjutants of infantry battalions) and soldiers who would have been mounted continue to wear spurs.

Field Marshal Montgomery recorded that on mobilisation (the procedure that takes place when an army move from peace to war) in August 1914, when he was a young officer with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, all officers' swords were sent to the armourer for sharpening. They were carried on active service in the first few months of the war but were quickly taken out of use amongst the infantry as the war became more static.

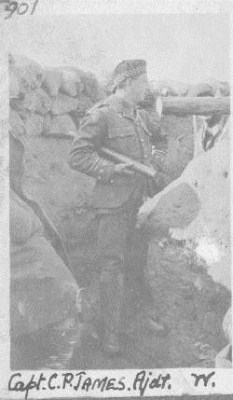

The Adjutant in the Trenches

The Adjutant in the Trenches

Here we see how the realities of the trenches impacted on the uniform. Captain CP James A&SH, was the Adjutant 1/10th (Scottish), The King's (Liverpool Regiment) although the Liverpool Scottish were a Territorial battalion he was a regular officer of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (which is what A&SH means). His rôle as Adjutant was to act as the Commanding Officer's executive officer and this made him senior to every other captain in the battalion.

He is pictured here probably sometime in early 1915 wearing glengarry, service dress jacket with breeches (as the adjutant, he would have had a horse for mobility and would not normally have worn a kilt) and some form of Wellington boot. The object under his arm is not a telescope but a trench periscope which meant that a soldier could look over the top of the parapet into 'no-man's-land' and toward the enemy trenches without exposing himself to an enemy sniper. When he came to France in 1914, he would have carried a sword (see the picture of his predecessor below) as part of his normal field service kit. Swords quickly disappeared in the trenches and officers carried a pistol and often a walking stick known as an 'ashplant'.

His rank is shown on his sleeve by the rings an by the three stars or 'pips'. More of these badges of rank can be seen here. He seems to have medal ribbons on the left hand side of his chest which might well represent service in the Boer War He was commissioned in 1900 and went on to command other infantry battalions winning two DSOs (the distinguished Distinguished Service Order was an award for bravery or distinguished conduct at a level immediately below that of the Victoria Cross) and was mentioned in the dispatches three times. A 'mention in dispatches' is a reward for brave or distinguished service which placed in the London Gazette, the British Government's own bulletin in which all official business is recorded. A soldier in the First World War who was 'mentioned in dispatches' was entitled to wear an oak leaf emblem on the ribbon of the Allied Victory medal.

The diaries below show that the Territorials were learning quickly how to adapt to war by reducing the kit that they carried. For example the officers took their swords to France in 1914 (as the Regular Army had done in August). They were quickly put into store [Regimental History]. In the photo detail on the right, taken at Tunbridge Wells in October 1914, Lieutenant Kendall of the Liverpool Scottish can be see with the uniform he would wear in the field with his sword hilt at his left hip.

It would not be too long before the Liverpool Scottish themselves had adapted their dress to the realities of trench warfare as this photo of Sergeant DAB Marples (right) shows.

November 19th 1914 - the Diary of Captain Bryden McKinnell:

"Battalion returned early very wet. Everything now became one wild rush, as we had to get and fit 400 boots, besides coats, tunic etc. we indented weeks ago for the stuff , but they never let you have things until you are absolutely going..... This has caused untold inconvenience and the men had to march off with new boots".

New boots ... would take time to break in and since the soldiers had to march nearly everywhere, this would be very painful for their feet and might make a soldier unfit for service. The battalion had gone to France equipped with shoes and gaiters, shoes which would be pulled off in the mud. The battalion's doctor was Captain Noel Chavasse, later to win the the Victoria Cross twice, and he took great trouble with the care of men's feet.

November 22nd 1914 - Diary of Captain Bryden McKinnell

"Met several [regular] officers coming home for their first leave wildly excited. They had been right there from the beginning. [August 1914]..... I noticed they carried all their kit in a small haversack. They looked very clean considering. Our kit has been getting gradually less".

Late November 1914 Liverpool Scottish Regimental History - Colonel A.M.McGilchrist

"The first sight the [Liverpool Scottish] had of a company of Regulars on the march was something of a shock. Many of the men had beards, their clothing was stained and muddy and quite a number were wearing cap-comforters instead of the regulation flat cap. Anything more unlike the traditional smart Tommy it would be difficult to imagine. But there was one thing about them that did particularly attract the eye. Every man's rifle was absolutely spotless, not a bad illustration for civilian soldiers of the distinction between the superficial and the essential'

Cap-comforter was a shapeless woolen tube with closed ends which can be formed into a hat or a scarf (still in use today). A Tommy short for 'Tommy Atkins', a traditional name for a British soldier

26th November 1914 - The Regimental History - Colonel A.M. McGilchrist

"[The Brigade Major] explained the [early] principles of trench warfare ... and issued instructions for routine to be carried out in the line. Some of these, in the light of later experience, were rather humorous. .... In the front line there will be no smoking whatever, and no matches will be struck ... Day and night, every other man will be on sentry duty.

The Brigade Major, the senior staff officer at Brigade HQ tasked with carrying out the the detail of the Brigade Commander's [a Brigadier-General] orders. The No smoking ban was because a lighted cigarette can be see from a long distance but the evidence of the writer suggests that this and the other instructions were completely impractical in the circumstances of trench warfare. For example sentry duty, required a duty of '1 in 2' or 'every other man' being responsible for keeping watch. This a very burdensome and impractical as men were needed to help with barbed wire, patrolling in front of the trenches, carrying stores and cooking and sleeping. The trench system would rapidly evolve as shown below.

Life in the Trenches

Routine and Sickness

The normal routine was three days in the trenches, xxxx days in the reserve trenches and xxx days out of line (but this often involved moving up to the line at night to form working parties for wiring or carrying parties for stores).

The Home Front

Christmas 1914 and Support from Home Christmas was spent out of the line when 'the mails were colossal' (250 sacks amongst less than 1000 men), a gift from Lord Derby of 'plum puddings for the men ... and a full Christmas dinner for the officers'. It is clear that the support from home for the Liverpool Scottish in Belgium was very significant. There were many supporters back in Liverpool and the Wirral to provide that which the Army could not or would not make available.

Christmas 1914 - The Regimental History - Colonel McGilchrist

".. Ladies' Committee ... worked indefatigably at the knitting and collecting of socks, cap comforters and cardigans ... "

Mr John Rankin gave £60 a month to provide extra rations for the men .... he combed England from one end to the other to provided the number [of Primus stoves] required"

"... a particular drug he [Lt NG Chavasse, the battalion's MO] required ... was ordered by cable from the United States and reached him [Chavasse] in a fortnight".

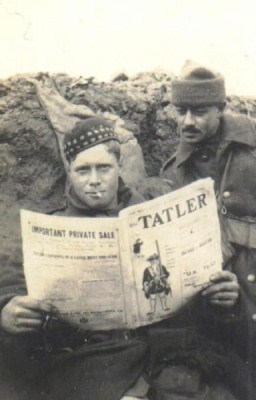

Home comforts find their way to the front

Daily newspapers could reach the front in Belgium on the day they were published in London.

Daily newspapers could reach the front in Belgium on the day they were published in London.

Cardigans - A knitted woollen jacket normally buttoning at the front (as opposed to a 'pullover' which is pulled over the head. Its invention is attributed to Lord Cardigan, commander of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War of 1854/55. By January 1915, soldiers were receiving goatskin jackets which were a great improvement but still left men cold and wet.

Primus stoves - This recognises the the need for being able to heat food in the trenches where it was often not possible to bring up rations during the day and only with the greatest difficulty at night. Braziers came into common use during January in the front line.

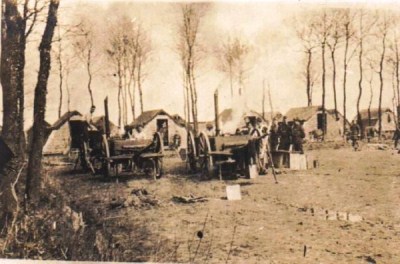

Efforts of the Battalion to helps itself

The battalion cookers are seen in action, probably in a rest camp out of the line in the Ypres Salient, possibly at Dickebusch. Regimental history makes very clear that the 'self-help' efforts of the battalion through the legitimate (and sometimes less-than-legitimate i.e. 'dodgy') initiative of individuals in key positions together with direct support from home (gifts and money) contributed enormously to the welfare (i.e comfort) and survival of the Liverpool Scottish through what was a very hard winter. The battalion's cooking arrangements are seen to the right with mobile cookers in position. When the battalion was in the line, food would often be cooked in a rear area and then carried forward through the trench system to arrive cold in the front line.

The battalion cookers are seen in action, probably in a rest camp out of the line in the Ypres Salient, possibly at Dickebusch. Regimental history makes very clear that the 'self-help' efforts of the battalion through the legitimate (and sometimes less-than-legitimate i.e. 'dodgy') initiative of individuals in key positions together with direct support from home (gifts and money) contributed enormously to the welfare (i.e comfort) and survival of the Liverpool Scottish through what was a very hard winter. The battalion's cooking arrangements are seen to the right with mobile cookers in position. When the battalion was in the line, food would often be cooked in a rear area and then carried forward through the trench system to arrive cold in the front line.

'self-help' efforts

- The Quartermaster's staff claimed to have been the first to divide rations into packs for so many men (in sandbags) to be distributed quickly at night at the forward dump.

- Somebody 'found' a sausage-making machine, presumably when it fell off the back of a passing lorry. This was reportedly a 'first' for any battalion in the BEF.

- Company Quartermaster Sergeant RA Scott McFie of Y Company published his own cook book 'Things That Every Good Cook Should Know'. In civilian life he was a fine scholar and a member of a prominent business family. The Museum holds some of his meticulously kept note books.

Lt (later Captain) Noel Chavasse, later to win two Victoria Crosses, was the battalion's medical officer (MO) from going overseas in 1914 until his death in August 1917.He made great efforts to maintain the health and morale of men in the line through a wide range of methods.

Cardigans - A knitted woollen jacket normally buttoning at the front (as opposed to a 'pullover' which is pulled over the head. Its invention is attributed to Lord Cardigan, commander of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War of 1854/55. By January 1915, soldiers were receiving goatskin jackets which were a great improvement but still left men cold and wet.

Cardigans - A knitted woollen jacket normally buttoning at the front (as opposed to a 'pullover' which is pulled over the head. Its invention is attributed to Lord Cardigan, commander of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War of 1854/55. By January 1915, soldiers were receiving goatskin jackets which were a great improvement but still left men cold and wet.

Primus stoves - This recognises the The need for being able to heat food in the trenches where it was often not possible to bring up rations during the day and only with the greatest difficulty at night. Braziers came into common use during January in the front line. We can see a brazier in use in the photo on the right. the brazier is simply a can with holes punched in it and can be see on the right of the picture.

Diary of Sgt DAB Marples: later Regimental Sergeant Major and was awarded the Military Cross as a Company Sergeant Major

Feb 26th 1915

"A glorious sunny day after a hard frosty night. Teague, another of my cheeriest boys in the platoon was shot in the head at noon whilst right beside me. A wretched day for my platoon, being peppered with enemy rifle fire from 20 yards away; sand bags being ripped away all day".

Sand bags (generally filled with earth) solidified the structure of the trenches and (although much larger) could be laid like bricks within headers and stretchers to give a bonded strength. In this case the enemy fire seems to be aiming to break down the strength of the sandbags and leave the occupants of the trench in greater danger.

Mar 5th 1915

"A fine day. Had a two hour march and parade in the forenoon and got leave with Sgt. Finnie to go to Poperinghe in the afternoon. Had a pleasant afternoon and a good English meal of steak and chips".

Poperinghe was a small Belgian town just behind the front line area which was relatively safe. It provided rest and recuperation facilities for tired Tommies at a variety of restaurants, cafes, estaminets and also, for much of the war, at the famous Talbot House run by the Rev. Tubby Clayton. However, the town of Ypres/Ieper remained in full swing through to spring 1915 although actually under fairly continual shellfire and about two miles from the front line.

Mar 9th 1915

"A fine day but very cold. Severe frost last night. Had a glorious bath and issue of clean underclothing and kilts stoved free from lice"

The phrase "kilts stoved free from lice" was a method of removing lice which developed very quickly in the trenches and were a great source of discomfort to soldiers.

Trench Life - Early 1915

The Commanding Officer: Lt Colonel JR Davidson is on the right of the picture firing a rifle grenade. Colonel Davidson's diary records that on the 20th March 1915 he went up to 38 Trench at Hill 60 (near Ypres/Ieper) to inspect a new loophole and he that he 'fired about 12 rifle grenades with a fair degree of success. He appears to be caught at the moment of firing the grenade as others in he group appear to be following its path through the air.

Rifle Barrel: The barrel of the rifle is by his left shoulder and he is trying to keep his head below the level of the muzzle (the business end of the rifle) to avoid the effects of the blast).

Personalities: Left to right the personalities are Capt. CP James (Adjutant and observing through armoured slit), to the immediate right is Capt. AS Anderson (Company Commander), an unknown private, Lt. Kenneth Gemmell and Lt Col JR Davidson.

Headdress: Soldiers are in a mixture of headdress and while most men are wearing the official glengarries with the diced (chequered) band, one is wearing the more practical woollen 'cap-comforter' which were already appearing by November 1914. The steel helmet was not introduced until later in the war and even then it was difficult to persuade soldiers to wear them.

Periscope: There are two 'trench periscopes' being used in the centre and they can be seen sticking up over the top of parapet. T he adjutant's (to the left) is in the form of a circular tube whilst the other seems to be a rectangular tube.

Armoured Loophole: To the left is a metal sheet with a slot cut in the bottom; this is an armoured loophole to allow a rifle to be fired with protection to the firer. There were a variety of methods of protecting observation points and loopholes. Soldiers appear to be watching to their front and to a point above them; a rifle grenade is being fired by the man in the right foreground who is, in fact, the Commanding Officer

Water Bottle: A water bottle can be seen to the bottom right; supplies of drinking water were a great problem particularly in the early days of trench warfare when there were very few communication trenches. However, at hill 60 the Liverpool Scottish so improved their position that it was possible to move the 400 yards between battalion HQ (dug into the banked sides of the Ypres to Comines railway line) and the front line positions.

Captain Anderson Ypres Salient, Spring1915

Sandbags: The photo shows a sandbagged trench. Sandbags were difficult to come by in 1914 so this suggests a later date. Sgt DAB Marples describes how the Germans shot at the sandbags at close range to break them down and reduce the cover that they gave.

Headdress: As the glengarry with diced (chequered) banding is still the headdress of choice but soldiers are still in gloves and greatcoats, this suggests Spring 1915. The soldier to the left in the standard peaked cap is not of The Liverpool Scottish but may be a member of an English battalion coming into or going out of the trenches, an artillery officer or possibly Lt Kidson RAMC. Quite quickly, the stiffening was taken out of the peaked cap as the very flat surface was more easily spotted from the air. Alternatively he might be one of the few Army Service Corps or Medical Corps soldiers attached to the battalion although the binoculars and the location in what appears to be the front line make this unlikely. This particular soldier is well wrapped up against the cold by his scarf; the binoculars that he carries may indicate that he is an officer or a Senior NCO.

Relief: This is the term used to describe the operation when one group of soldiers replaces another group at a particular position. The 'relief' of one battalion by another in the front line is a difficult operation. At the early stages of the war (when there were few communication trenches) it was particularly dangerous. One method was for the new battalion to cross in the open to their new trenches, line up behind and drop in. The outgoing soldiers then climbed out of the back of their trench into the open. This was rather noisy and dangerous for troops in the open but it did give people a chance to find out about the trenches from the previous occupants. An alternative was for the new soldiers to move in at one end while the other soldiers left at the opposite end. There was more protection from the enemy but the new soldiers found out nothing about the new trenches which would almost certainly lead to casualties from snipers.

A Wider View

As part of the Centenary Commemorations Major I.L. Riley has written a series of articles recounting the experience of the Territorial Force during the First World War. A more indepth article on the Winter of 1914-1915 can be found here.

Previous page: Mobilization

Next page: Hooge 1915