The Development of Trenches

Development of Trench Defences

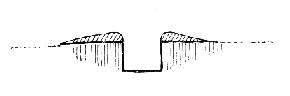

There are a number common ideas about trenches which are wrong. The idea that the whole of the First World War was lived out in complex systems of trenches, all connecting with networks of covered approaches and dugouts (deep covered shelters) is wrong. In the earliest days of the war, fighting was mobile and only afterwards, when the situation became more static, were the first trenches built. As can be seen to the right they were shallow, very simple and crude.

There are a number common ideas about trenches which are wrong. The idea that the whole of the First World War was lived out in complex systems of trenches, all connecting with networks of covered approaches and dugouts (deep covered shelters) is wrong. In the earliest days of the war, fighting was mobile and only afterwards, when the situation became more static, were the first trenches built. As can be seen to the right they were shallow, very simple and crude.

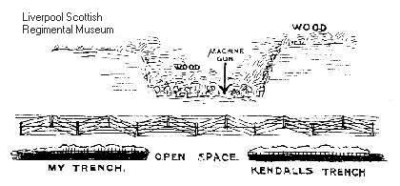

Later, during the middle of the war the very complicated system trench came into being. However, later again (1918), through increased mobility and lack of manpower, the trench systems became disconnected once more with big gaps between trenches of perhaps over a quarter of a mile (400 metres) with machine gun posts in between.

The Regimental History - Colonel A.M. McGilchrist

"The siting of the British trenches was quite haphazard, the line on which a counter-attack had been held up ..... frequently becoming the fire trench with no regard for field of fire or even to the direction of the enemy ...... Many were open to enfilade fire, either from rifles or artillery";

"There was no trench system .... as in 1916. The front line of trenches was the only line and it was [not] continuous. Support trenches did not exist"

With men digging in where they had stopped enemy advances the whole front-line or Fire-trench was often miss-aligned to both the location of the enemy and the prevaling terrain. This meant tht the trench was open to enfilade fire. Infantry armed with rifles and larger Artillery could fire along the trench, redering them all but useless, obviously this is a very dangerous situation. The whole trench system included, support trenches which held men in reserve in case the front line is attacked and communication trenches allowing protected routes between the different main trenches.

Diary of Captain Bryden McKinnell

Nov 26th 1914:

"Made charcoal all day to be used in the trenches like the Japs did, that is a little smouldering in a bucket with a blanket over, no smoke is visible".

Nov 27th 1914

"One officer ... got sniped last night .... The snipers are bad - they get right behind our trenches dressed in our khaki uniform. We shall probably be here for days - not a jolly outlook! Only one machine gun is required , where the line is within thirty yards of the enemy".

Charcoal was at this tstage an important source of heat in the front-line. Made by partially burning wood it burns hot but without a flame and little smoke, and thus hidden from the enemy. This trick was apparently learnt from the Russo-Japanese war of ten years earlier. Many lessons were drawn from the Russo-Japanese war regarding trench warfare and the employment of artillery and machine guns. A brazier is show below. The British army nolonger wore the bright red as at Waterloo but khaki a brown colour which had replaced the traditional scarlet or red some thirty years previously for field or service uniforms (Hindi - 'dust'?).

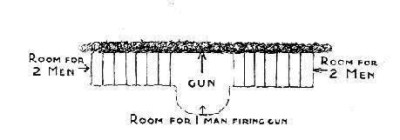

December 12th 1914 shows his machine gun position

McKinnell's ideal Gun Position

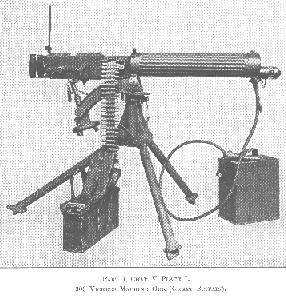

A Vickers Machine Gun. The type McKinnell used

The machine gun: in this case the Vickers Medium Machine Gun which had been recently introduced to the British Army. Firing 550 rounds per minute to a distance of 2900 yards (about 2700 metres) fed by belts of 250 rounds. With a 'dial sight' it would reach targets at 4500 yards (4100 metres) which were not visible from the gun. Captain Bryden McKinnell was the machine gun officer. There were two machine guns per battalion and this was soon increased to four. Their importance to the battalion is underlined by McKinnell's comments in his diary that he thought the success or failure of the battalion might rest on his guns.

On 30th November the Battalion suffered its first casulty. Captain Twentyman returning from collecting some 'jam tin' bombs, an improvised explosive used in the close confinds of the trenches, was hit by a sniper, a trained marksman who would lie hidden waiting to shoot soldiers who carelessly exposed themselves with a single shot.

Winter 1914/15 - The Regimental History - Colonel A.M. McGilchrist

" ... it was only 35 yards [33 metres] to the enemy ... the parapet was repaired at night but it was not strong and Captain Twentyman realised that if it did not hold, the whole position would be enfiladed from the German position on higher ground .... the sniper doing the damage was [close] and as soon as it was light ... Capt. Twentyman went down through the trench ... to an RE dump to get a 'jam tin' bomb with which to dislodge him .... he came back over the open instead of up the trench thinking .. that a thin hedge would screen him .... he was seen and shot down.

Diary of Captain Bryden McKinnell

Nov 30th 1914

"Poor ... Twentyman was our first casualty ... it was a terrible business to get him out [of the trenches]. However they will manage to get the wounded out, I don't know".

Improvised Bombs

Bombs (or grenades) were thrown by hand or fired from the end of a rifle and became very useful in trench warfare. They were in short supply and especially at the beginning of the war they were improvised ('home made') literally from empty tins of jam which came with the rations.

The shortage of bombs was a cause of considerable difficulty during the Liverpool Scottish attack at Hooge in 1915 when the battalion received only 400 including 150 of the newly invented Mills Bomb.

At the front many types of bomb were improvised. The jam tin bomb might use half a pound (250 gm) of dynamite or gun-cotton surrounded by pieces of iron all stuffed into a used jam tin (really!). The bomb was set off by lighting piece of safety fuse cut long enough to ensure the safety of the thrower but short enough to ensure it didn't get thrown back by the enemy. This Liverpool Scottish soldier is seen in the trenches in early 1915 carrying what appears to be a 'jam tin' bomb in his right hand. Trench warfare in which the enemy was often engaged at ranges of 20 yards (just under 20 metres) or less had suddenly thrown up a need for short range explosive devices which could be used quickly against the enemy. A more powerful improvised hand grenade which seems to have consisted of a sacking container containing scrap metal and stones with the explosive charge contained in a jam tin inside.

At the front many types of bomb were improvised. The jam tin bomb might use half a pound (250 gm) of dynamite or gun-cotton surrounded by pieces of iron all stuffed into a used jam tin (really!). The bomb was set off by lighting piece of safety fuse cut long enough to ensure the safety of the thrower but short enough to ensure it didn't get thrown back by the enemy. This Liverpool Scottish soldier is seen in the trenches in early 1915 carrying what appears to be a 'jam tin' bomb in his right hand. Trench warfare in which the enemy was often engaged at ranges of 20 yards (just under 20 metres) or less had suddenly thrown up a need for short range explosive devices which could be used quickly against the enemy. A more powerful improvised hand grenade which seems to have consisted of a sacking container containing scrap metal and stones with the explosive charge contained in a jam tin inside.

The enlarged picture (click on it) includes a soldier sniping although this seems to be a posed shot.. He is firing through a pipe which will go through the parapet of the trench. In this way he hopes to avoid detection. The 'Notes on Field Defences (1914)' suggest a number of ways of protecting the sniper.

There was a 'hair brush bomb' which was basically a paddle-shaped piece of wood with explosive tied to the broad end. Below, a 'stick bomb' is thrown by Cpl Bartlett of the Liverpool Scottish (posed) in forward trenches at Zillebeke in early 1915. Cpl. Bartlett was later killed during the Battle of Hooge (about 4 km east of Ypres - June 16th 1915) whilst he was involve in bombing during the attack. Although he has no known grave, a German officer returned his effects after the end of the war and recorded that Bartlett had been buried by the Germans near the east end of Railway Wood.

Diary of Captain Bryden McKinnell

Dec 1st 1914

" .. enemy attacked [us] twice ... beaten off wit heavy loss, also accounting for several snipers. They were very bold creeping at night right up top our trenches .. we couldn't put our heads up as the snipers ... directly in front of us five or six yards away, would immediately have potted us".

Dec 7th 1914

[In the trenches] "Busy making fascines .... except for heavy artillery duel, everything quiet ... having a bad time in the trenches on account of rain breaking earthworks .. Went up to the trenches at night with Adjutant .... snipers sniped at us all the way .... Trenches in a terrible mess and all falling in, deep in water"

The trenches occupied by McKinnell in the Kemmel area were very close to the enemy front line. His diary of December 9th 1914 shows these trenches 60 yards from the German line in most places and 30 yards in others.

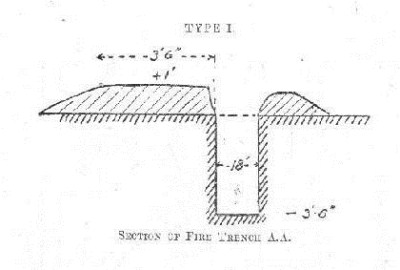

McKinnell's diagram (below) showing the ideal trench is taken from the printed version of his personal diary (Tuesday 8th December 1914).

McKinnell's diagram (below) showing the ideal trench is taken from the printed version of his personal diary (Tuesday 8th December 1914).

He records that the regulation trench was supposed to be.. 'three feet (about 1 metre) [across] and three feet [deep] with an eighteen inch [about half a metre ] parapet with fire recesses and [allowing] for a certain degree of comfort'.

He records that the regulation trench was supposed to be.. 'three feet (about 1 metre) [across] and three feet [deep] with an eighteen inch [about half a metre ] parapet with fire recesses and [allowing] for a certain degree of comfort'.

The trench he was actually occupying on that day was .... 'seven feet wide and two feet deep, plus one yard (three feet) of mud and a small parapet with no loopholes. A stream of water ran the whole length of the trench so I have to have every second man baling water out; as it was two or three men were up to their waists. It rained all the time, and every ten minutes seemed like an hour'.

Snipers were a ever present danger making life extremely difficult. Either in their own trenches or lying out in no-man's land and prepared to wait all day for their victim, no soldier in the trenches opposite dare expose himself. Casualties were often the result of carelessness. The trenches occupied by McKinnell in the Kemmel area were very close to the enemy front line. Bryden McKinnell's diary of December 9th 1914 shows these trenches 60 yards from the German line in most places and 30 yards in others.

A trench normally had a parapet, a raised bank of spoil (earth or earth in sand bags) in front of the trench to provide extra cover. Fascines were bundles of wood wired together which were placed at the bottom of trenches for soldiers to stand on. (Also later used on a larger scale to fill ditch/trench obstacles to allow tanks to cross).

Artillery came in a range of sizes, heavy artillery was artillery of greater firepower than the standard artillery gun used to support the infantry which was an 'eighteen pounder' (the weight of its shell - about 8 kg). Heavy artillery was less mobile and about t is time the Germans started shelling the town of Ypres with a shell of diameter 17 inches (between 40 and 45 cm and the sort of shell that could be fir d by the main guns of a battleship).

Despite the rudimentary nature of the Liverpool Scottish trenches at Kemmel, the Army was already taking on board the need for making use of available features such as sunken roads. In Spring 1915, the CO of the Liverpool Scottish, Lt Col JR Davidson was to set a new standard in the construction of dugouts in the area around Zillebeeke using his civilian experience as a professional engineer.

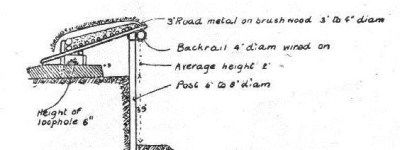

Below is a diagram of a field defence built into the side of a sunken road. It is taken from the hurriedly produced Army pamphlet 'Notes on Field Defences - 1914' and demonstrates the urgent need to build up expertise in improvising defences and to pass on the information gained from experience in France and Flanders in the first few months of the war. The Liverpool Scottish quickly acquired this expertise under their commanding officer, a professional engineer.

Trenches and Field Defences in 1914

Measurements

The measurements on these diagrams are given in feet and inches so 3' 6" means 3 feet 6 inches. There are 12 inches in one foot. Three feet is just under one metre and one foot is about 30 cm.

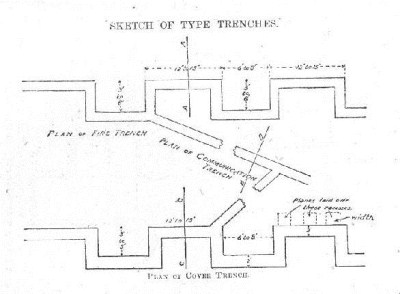

The System

The diagram of the trench system shown on the left shows 'traverses' which are changes in direction in the trench line ( a sort of square zigzag) which would happen approximately every four yards (4 m). Fire and cover trenches did not go in long straight lines. This reduced the effects of an explosion in the trench and meant that the enemy could not fire far along the trench. The walls of trenches would be reinforced (revetted) with wood or other materials to stop them blowing in and collapsing under shellfire.

The diagram of the trench system shown on the left shows 'traverses' which are changes in direction in the trench line ( a sort of square zigzag) which would happen approximately every four yards (4 m). Fire and cover trenches did not go in long straight lines. This reduced the effects of an explosion in the trench and meant that the enemy could not fire far along the trench. The walls of trenches would be reinforced (revetted) with wood or other materials to stop them blowing in and collapsing under shellfire.

The Type 1 fire trench on the right (the type shown at the top of the diagram above) is quite narrow given that it would have to hold a soldier with all his equipment. The enemy side would be to the left; there is a one foot parapet. There is another earth bank behind the trench (the parados) to stop back blast from enemy shells. As the depth below ground is 3 foot 6 inches and the parapet is one foot above ground, the total cover was 4 foot 6 inches about 1,4 m). An average man might be 5 foot 8 inches high (about 1.72 metre ). Many soldiers were shot in the head by snipers because they accidentally showed their heads above the parapet.

The Type 1 fire trench on the right (the type shown at the top of the diagram above) is quite narrow given that it would have to hold a soldier with all his equipment. The enemy side would be to the left; there is a one foot parapet. There is another earth bank behind the trench (the parados) to stop back blast from enemy shells. As the depth below ground is 3 foot 6 inches and the parapet is one foot above ground, the total cover was 4 foot 6 inches about 1,4 m). An average man might be 5 foot 8 inches high (about 1.72 metre ). Many soldiers were shot in the head by snipers because they accidentally showed their heads above the parapet.

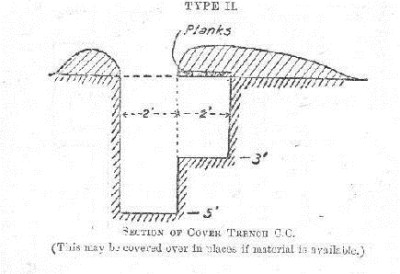

A Type 2 cover trench might be behind the fire trench (seen at the bottom of the first diagram). These could also be traversed but would be deeper. The diagram to the left shows them 5 feet deep with a covered recess for sitting or sleeping which would be 3 feet deep. The cover recess would be on the enemy side.

A Type 2 cover trench might be behind the fire trench (seen at the bottom of the first diagram). These could also be traversed but would be deeper. The diagram to the left shows them 5 feet deep with a covered recess for sitting or sleeping which would be 3 feet deep. The cover recess would be on the enemy side.

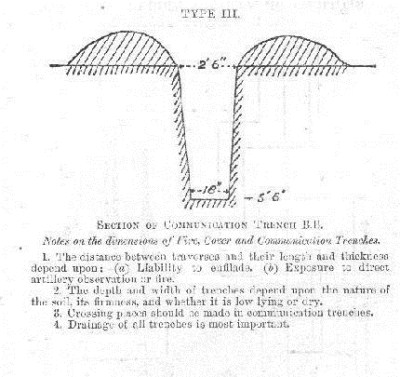

The Type 3 communication trench shown on the right connected the front line fire trenches to the cover trenches. At a width of 18 inches at the bottom an possibly full of mud, it would be very difficult to carry stores up to the line and the wounded back and even more difficult if the men going forward had to pass the men going back. These trenches were deeper so that men could walk upright. Often, because of flooding or congestion, soldiers took the risk of crossing open ground instead of using the communication trench.

The Type 3 communication trench shown on the right connected the front line fire trenches to the cover trenches. At a width of 18 inches at the bottom an possibly full of mud, it would be very difficult to carry stores up to the line and the wounded back and even more difficult if the men going forward had to pass the men going back. These trenches were deeper so that men could walk upright. Often, because of flooding or congestion, soldiers took the risk of crossing open ground instead of using the communication trench.

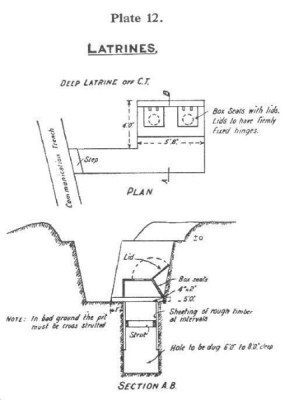

Latrines It was not just the fighting positions and communication trenches which needed digging but the more prosaic everyday requirements of Latrines (Toilets). Similar examples are still used today on active service.

The source of the diagrams above is the Army Publication 'Notes on Field Defences - 1914'.

Previous page: Sketches

Next page: Personnel Stories