Come on the Lions: Another Bitter Winter

‘Come on the Lions’: Another Bitter Winter War of Raids and Patrols

Ian Riley, Liverpool Scottish Museum Trust

KORLR: King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment)

KLR: King’s (Liverpool Regiment)

LF: Lancashire Fusiliers

SLR: The South Lancashire Regiment

LNLR: Loyal North Lancashire Regiment.

1/4 KORLR is therefore 1/4th Battalion, King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment) - 1000 men at full strength [1/4th is said as ‘First Fourth’]. 55th Division had three infantry brigades, each of four battalions, 164, 165 and 166 Brigade.

The Territorials of the 55th (West Lancashire) Diision had seen action on the Somme in August and September 1916 around Guillemont and Morval. In October, they transferred to perhaps the hottest spot on the Western Front, the Ypres Salient. There they would train for the Third Battle of Ypres (often known, incorrectly, as ‘Passchendaele’) beginning on 31st July 1917.

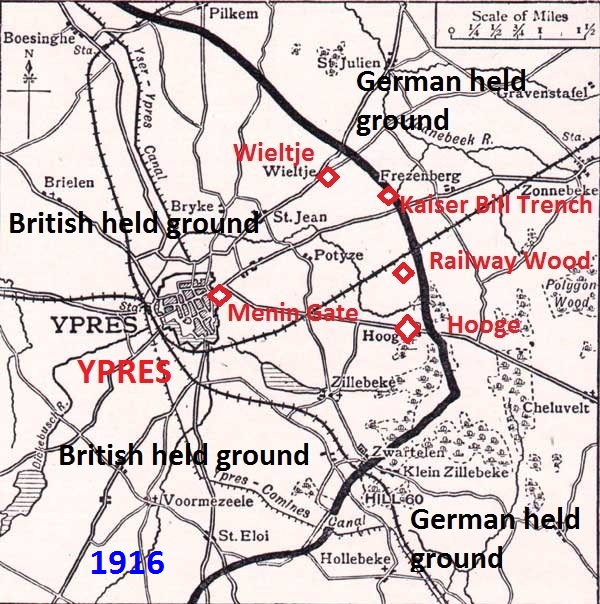

Belgium’s ancient moated and walled city of Ypres (Ieper in Flemish) is the centre of a semicircle of low hills a few miles to its east. Whilst the hills may be low, they command the city set in the otherwise flat Flanders countryside. The front approximated to the crest of these hills so that the British line jutted into German-held territory. This bulge was the infamous ‘Ypres Salient’ or simply ‘The Salient’. The Germans looked down and could fire from three sides onto Ypres. The Salient was a place more dangerous than most. The famous Cloth Hall of Ypres (the cathedral-like wool trading hall, finished 1304) was progressively demolished leaving the great tower just a stump; it took until 1967 to restore.

Belgium’s ancient moated and walled city of Ypres (Ieper in Flemish) is the centre of a semicircle of low hills a few miles to its east. Whilst the hills may be low, they command the city set in the otherwise flat Flanders countryside. The front approximated to the crest of these hills so that the British line jutted into German-held territory. This bulge was the infamous ‘Ypres Salient’ or simply ‘The Salient’. The Germans looked down and could fire from three sides onto Ypres. The Salient was a place more dangerous than most. The famous Cloth Hall of Ypres (the cathedral-like wool trading hall, finished 1304) was progressively demolished leaving the great tower just a stump; it took until 1967 to restore.

Front-line battalions were beyond Ypres but each brigade’s reserve battalion was billeted within the city, some underneath the massive defensive ramparts themselves. Huge brick-lined tunnels, known as ‘The Casemates’, were part of the original 1680 structure. The Lancashire Infantry Museum holds a witness account of 1/4th Bn., Loyal North Lancs, Preston’s Territorial infantry, used in their excellent ‘War History’. An unknown hand, with fresh memory, wrote:

These ramparts billets merit special description. The city of Ypres is guarded on the east by a rampart and moat – this rampart being about 50 feet high and of equal thickness and formed of the earth taken out when the moat was dug and faced with brick …. Under this [casemates] had been excavated – stuffy, cramped places filled with frames and props, dimly lit by electric light and generally overcrowded and always damp and rat infested – but places where the … reserve could lie down and sleep in comparative safety except for the danger of gas.

These ramparts billets merit special description. The city of Ypres is guarded on the east by a rampart and moat – this rampart being about 50 feet high and of equal thickness and formed of the earth taken out when the moat was dug and faced with brick …. Under this [casemates] had been excavated – stuffy, cramped places filled with frames and props, dimly lit by electric light and generally overcrowded and always damp and rat infested – but places where the … reserve could lie down and sleep in comparative safety except for the danger of gas.

Of the casemates used for accommodation and formation HQs, he wrote:

To the south of the Menin Gate, an ugly gap in these ramparts … was one of such [casemates] usually occupied by two companies, to the north another and a small nest of dugouts used for the officers. …. On the night of a relief – men would arrive in small parties in the pitch dark and stumble along the street which was always a foot deep in mud until they found the gas sentry when they would disappear within the dark entrance with a sigh of relief.

The 55th Division required serious reinforcement. Soldiers were arriving with just sixteen weeks of UK training and a short ‘welcoming’ top-up in France at the infamous depôts in Etaples, the ‘Bull Ring’. This had many training facilities but a reputation for bullying instructors with yellow armbands, known as ‘canaries’. The lack of regimental structure, essential for morale, often left inexperienced soldiers desperate to get to the front. Pte Alexander Booker, of the Liverpool Scottish (1/10 KLR), conscripted August 1916 and arriving in France on 4 January 1917, wrote:

5/1/17: Army sausages become palatable [Irony after two days travel from Oswestry, presumably with sparse rations]. 7/1/17: Sunday not recognised here. First visit to Bull Ring. Grim reality of war brought home by the numbers of Wooden crosses … [Big Base hospitals were nearby] … Wrote home. Oh for the Old English Sabbath [He was a clerk and a Methodist lay preacher back in Liverpool].

After Etaples, disliking both town and citizens, he moved forward to Poperinghe only to move back to ranges near St Omer. He finally arrived with his battalion in mid-February:

23/1/17 At Reinforcement Camp, Poperinghe. Saw Taube plane [German] under fire for first time. 26/1/17 Left Poperinghe for Nort Leulinghem Second Army School of Musketry. 1/2/17 Commenced Firing Course. 2/2/17 Coldest day ever experienced, boots frozen, blankets white. Oh for home. 4/2/17: “A day of rest and gladness”. A hard day’s work at [camp]. Oh for an Old time Sabbath.17/02/09 Reveille 3.45. Left 6am arrived … joining the battalion.

Booker took over six weeks to reach 1/10 KLR from training with 3/10 KLR in Oswestry. Once at the ‘front’, inducting new arrivals was generally gradual, with men perhaps held for a week at Divisional Reinforcement Camp for assessment and remedial training. Once with their units, there might be front-line day or night working parties before a ‘full-time’ posting to their company. 2Lt GD Morton, (1/10 KLR) wrote to his wounded CO six weeks after their costly Guillemont battle:

I’m training and putting the wind up a draft of 70 of our own men and 14 officers so I have my hands full … took a stroll over to Guillemont [where we charged]. It is an awful mess, and for yourself alone, Colonel, some of our men have not even been buried yet, and are nothing else but bones.

Front line spells varied but were often only four days but longer (two or three weeks) during major summer offensives. Infantry probably spent about 25% of their time in the front line but in difficult conditions, especially in winter. Directly east of Ypres and just north of the Menin Road was Railway Wood. The 55th Division held up to 5000 metres (alternating with other divisions) running north from Hooge on the Menin Road through Railway Wood to Wieltje. The anonymous veteran of 1/4 LNLR wrote:

Railway Wood … was a tumbled mass of blue grey mud, honeycombed with slimy tumble-down trenches … with a few tree stumps … trenches were always being blown in by trench mortars and always under repair – miners and tunnellers worked incessantly … front line companies had a poor time at best – still worse for the unfortunate men who manned the isolated shell hole posts [forming] the right of the line … support companies lived in comparative comfort in BEEK Trench – until the Hun discovered that he could enfilade it from both flanks. Even in quiet times, the place was horrid – in times of stress it was a nightmare.

Trench warfare changed. The German lines, after huge losses in 1916, shortened drastically south of Ypres. Their defensive strategy changed to a system of six lines to break up and delay attackers. The BEF revised tactics, improving the application of artillery and providing more Lewis Guns, a portable platoon machine gun. In spring 1917 platoon structure changed, with greater responsibility for platoon commanders and emphasis on their training. The attack became based on platoon fire and manoeuvre supported by close artillery. Much of early 1917 was spent training in these new tactics. Fighting around Railway Wood often involved the blowing of mines to create craters then immediately seizing the lip, improving observation. The War History of 1/4 LNLR describes some changes:

We no longer hold the line continuously [in the Salient] … numbers are too small – but with a certain number of sentry posts, each … an NCO and when possible, six men – more often four – some posts being Lewis gun posts, others bombing posts, others riflemen only. This line of posts, weak though it is, is strung out between and in front of a series of strong points containing machine guns and an infantry garrison lodged in deep mines, while behind us is the support company ready to come up in case of need and reserve troops further back; [additionally] the guns [on call by telephone or rocket]

The 55th Division did more than line-holding and training. Aggressive patrolling dominated No Man’s Land. Patrols were expected to engage the enemy as encountered, almost no matter how out-numbered:

A patrol leader’s report containing a reference to “enemy seen” raises a perfect hail of questions from higher authority, truculently asking why they were not instantly gone for and spitted. (War History 1/4 LNLR)

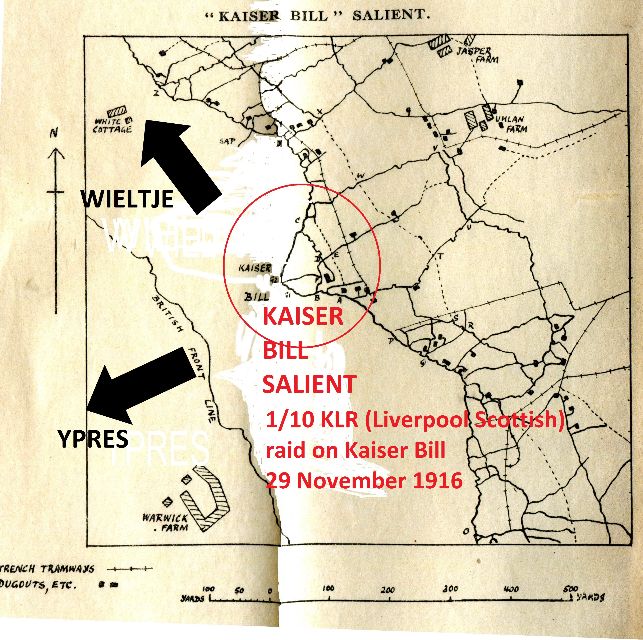

Carefully prepared raids carried fighting to the enemy. Parties up to 200 caused mayhem, took prisoners and eroded enemy morale. 1/10 KLR raided ‘Kaiser Bill’ trench (Wieltje) in November 1916. Equipment and roles were detailed for all 86 men. Three weeks’ work brought success but training was so realistic that one man was killed and 11 wounded when a bomb exploded prematurely.

Carefully prepared raids carried fighting to the enemy. Parties up to 200 caused mayhem, took prisoners and eroded enemy morale. 1/10 KLR raided ‘Kaiser Bill’ trench (Wieltje) in November 1916. Equipment and roles were detailed for all 86 men. Three weeks’ work brought success but training was so realistic that one man was killed and 11 wounded when a bomb exploded prematurely.

A bigger raid with 200 men from 1/4th King’s Own launched on 23 December 1916. Intensive rehearsals took nearly a month. The historian of the 1/4 KORLR wrote:

These rehearsals were very practical in their value. A replica … of the enemy’s position … was marked out by tapes on the practice ground and times and distances were carefully noted. A full and final rehearsal on 21 December … and [the] raiding party of 200 [was] inspected by Sir Douglas Haig.

The Germans had evacuated their trenches: the raiders were caught in immediate defensive fire. Casualties were 11 killed and perhaps 25 wounded. Summarising the recently published history, The Lion and the Rose, using the Barrow Times as a source:

LCpl James Little from Millon was seriously wounded in the left side and lying in No Man’s Land. His Ulverston friend, Pte Cuthbert Whalley, the first to reach the German trench, was hit by shrapnel as he climbed the parapet. Refusing help, he encouraged others with shouts of ‘Come on, the Lions’, before limping back to British lines. He found Little and carried him on his shoulders to British lines, only accepting treatment when stretcher-bearers took over, His friend (Little) died at Lijssenthoek, site of large Casualty Clearing Stations near Poperinghe [The Lion and the Rose]

James Little lies at Lijssenthoek amongst 10,000 soldiers and Staff Nurse Nellie Spindler (died of wounds received near Ypres, August 1916). Whalley recovered, returning in May 1917 but, posted to 8 KORLR, was killed within two days.

In the spring of 1917, more Lancashire Territorials arrived in France and Flanders. The 42nd (East Lancashire) Division returned from Egypt and Sinai (having previously been in Gallipoli) and the two second line divisions on Home Defence in the UK, the 57th (West Lancashire) Division and the 66th (East Lancashire) Division finally left England in February for France.

Further reading and thanks:

The War History of1/4 LNLR: 1921

The Lion and the Rose (1/4 KORLR): Kevin Shannon 2015

The Lancashire Infantry Museum www.lancashireinfantrymuseum.org.uk

The Long Long Trail www.longlongtrail.co.uk

Previous page: Digging for Victory

Next page: Territorials Battle Desert Heat and Germany’s Air Aces.