From Home Defence to the Suez Canal 1914

The East Lancashire Division of the Territorial Force moves to relieve the Regular Army in Egypt.

First Territorial Force division to go overseas

It Ain’t Half Hot, Mum

Manchester Territorials join the Camel Corps

|

Acknowledgement: Quotes from the letters of individual soldiers in this article (originally appearing in the local press) relate to the 1/9th Bn., The Manchester Regiment based in Ashton-under-Lyne and appear on the excellent ‘Ashton Territorials’ website of Linda Corbett |

We will follow the East Lancashire Division’s rapid and unexpected departure for Egypt just six weeks after mobilisation - hardly time to buy sun-cream. Meanwhile, West Lancashire units were guarding ports and railways, moving to France and Belgium from November 1914 onwards.

We will follow the East Lancashire Division’s rapid and unexpected departure for Egypt just six weeks after mobilisation - hardly time to buy sun-cream. Meanwhile, West Lancashire units were guarding ports and railways, moving to France and Belgium from November 1914 onwards.

The members of the Territorial Force [TF] were responsible only for home defence of the UK; their ‘obligation’ went no further. By 1914, less than 10% had opted for overseas service. In North-West England there were separate divisions for East and West Lancashire, two Cumbrian Border Regiment battalions and some specialist units. A divisional establishment was about 20,000 but they were about 7% and 15% under-strength. Some Territorials were under 19, too young for active service.

It was planned that both divisions would, within five days of mobilisation, replace Regulars in Ireland, open to coastal raids and where civil war threatened. Even before 1914 it was considered that this rushed two-way movement was unworkable. The actual change of plan was only made the day after mobilisation; Manchester Regiment billeting parties had already left for Limerick. The Lancashire divisions stayed in England with no definite rôle.

The East Lancashire Division was nearly full strength with twelve battalions from the Lancashire Fusiliers, the East Lancashire Regiment and the Manchesters (the latter two are now part of the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment) as well as RA (e.g. the Bolton Artillery), RE, Army Service Corps and the RAMC. Drill halls spread from Wigan, Bolton, Blackburn, Burnley, Bury, Oldham, Rochdale, Manchester with Hulme and Ardwick, through Salford to Ashton-under-Lyne. The East Lancashire Territorial Association, responsible for equipment, beat the starting gun three days before mobilisation, ordering immediately 2000 uniforms with another 2000 uniforms, 5000 pairs of boots and a 10% surplus of greatcoats to follow: Manchester men would not be at the back of any queue. Horses, harness and carts were ‘borrowed’ everywhere, councils lost water carts and a shop’s name was still visible on a medical cart in Egypt in 1917. Anything could be commandeered: a sword-waving Territorial officer stopped a London bus (with passengers) to collect 250,000 rounds of ammunition. In the first month of the war, the East Lancashire Association spent £37,780 on equipment. One gold sovereign (£1 coin) costs £220 today, making that almost £8 million, about £400 per soldier, possibly more.

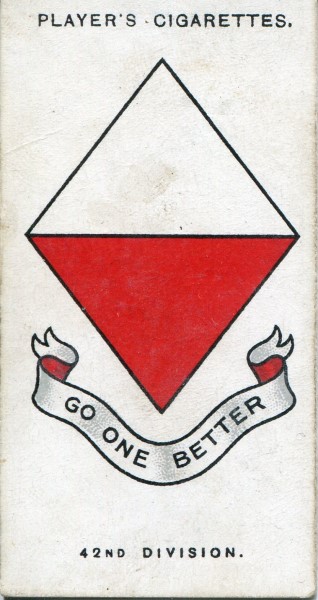

Egyptian rumours were common but less believable than those of Russians in Britain with snow on their boots. Nevertheless, on 5th September, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener sent a note wishing the division well in Egypt and encouraging hard training ‘so that it could soon go to France’; the 1915 Gallipoli campaign was not yet even a dangerous twinkle in Winston Churchill’s eye. Having been reinforced by recruits and from the National Reserve, 15,500 men of the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division sailed from Southampton for Egypt before midnight on 10th September, lights doused and with Royal Navy escort, the first Territorial division to leave the UK. To ensure a good party, ‘A’ Squadron of the Duke of Lancaster’s Own Yeomanry was included.

From Gibraltar, Private Fogerty told his wife that at sea he had to ‘fall in four times a day - once for physical drill. … The grub on board is very good, and we get plenty. … They want to 'nocolate' me, but I don't think. … learning all about a rifle, so they intend making me into a soldier.’ Inoculation was often resisted, officers complaining that Territorials were sufficiently educated to question it. Basic musketry was done at sea; this was a division to be trained, not yet ready for France.

They steamed into Alexandria on 25th September. The band aboard a (neutral) United States battle-cruiser played ‘God Save the King’. Manchester Territorials, uncertain of the US anthem, played ‘Marching Through Georgia’, appropriate perhaps because of Manchester’s cotton trade but possibly upsetting to American sailors from northern ‘Union’ states.

Why was the 42nd Division in Egypt? Egypt had been loosely allied to Turkey (the Ottoman Empire) but when the Suez Canal was built, the vital link between Britain and India, the British established ‘a sphere of influence’; today we might say ‘control’. Egypt’s ruler, the Khedive, remained but his power was British power, backed by our Regular soldiers who were needed in France; the 42nd Division covered.

Why was the 42nd Division in Egypt? Egypt had been loosely allied to Turkey (the Ottoman Empire) but when the Suez Canal was built, the vital link between Britain and India, the British established ‘a sphere of influence’; today we might say ‘control’. Egypt’s ruler, the Khedive, remained but his power was British power, backed by our Regular soldiers who were needed in France; the 42nd Division covered.

Troops dispersed to Cairo and Alexandria (about 100 miles apart) with some far south in the Sudan. All tropical kit was aboard a single ship; it was some time before light cotton replaced heavy wool. Khaki sun-helmets, ‘pith helmets’, gained much divisional favour and their history records:

Lancashire Territorial: “Bill, will they let us tak these whoam wi’ us?”

Bill: “Tha’ll be lucky if thee taks thy ‘ed whoam”.

Veterinary surgeons were hard pressed. Nearly 50 out of about 750 horses had died at sea for want of enough grooms and adequate horse-mastership. On landing, one hard pressed vet delivered an abusive reply to a civilian thought to be asking too many questions; he was, in fact, the C-in-C, Sir John Maxwell.

The versatility of the Territorials, a man for any job, was demonstrated when a company of the 7th Battalion of the Manchester Regiment (from Burlington Street) took over 70 camels and the rôle of the Camel Corps at very short notice. With a five-minute handover and a lot of documentation in Arabic, the company commander asked, with no great expectation, if any man had ‘camel experience’; taking a sharp pace forward was the camel-keeper of a Manchester zoo.

During October, in a period of ‘rising tension’ and Turkish manoeuvres on the border, 9000 Territorials made a show of strength through Cairo although pro-enemy factions suggested that a single unit marched in circles, a feeling with which every soldier might claim to be familiar. Although then still at peace with Turkey, war was declared on 5th November by which time units of the 42nd Division had been pushed forward to the Canal Zone into an operational role. The Egyptian war became ‘hot’ in February 1915 and Gallipoli lay beyond. We leave the men of the 42nd Division decorating their palm trees for Christmas and eating plum pudding.

Back in the UK some battalions of the West Lancashire Division and of the Cheshire Territorials had already reached the Western Front and many were preparing to go. By the end of 1914, some 36 British Territorial units were in France and Belgium with another 23 scheduled to sail in February.

Previous page: Training for the Great War

Next page: Reservists in the Firing Line 1914