Territorials Battle Desert Heat and Germany’s Air Aces.

Ian Riley, Liverpool Scottish Museum Trust

42nd (East Lancs Division) Fights Both Heat and Enemy in the Desert in 1916

In the spring of 1917, more North West Territorials arrived in France and Flanders. The 42nd (East Lancashire) Division returned from Egypt and Sinai (having previously been in Gallipoli) and the two second-line divisions on Home Defence duties in the UK, the 57th (Second West Lancashire) Division and the 66th (Second East Lancashire) Division finally left England in February for France. In the air, many Territorial Force (TF) officers and men found their way into the rapidly expanding Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and, as well as the 42nd Division, we look at some of these airmen 100 years after possibly the lowest point of the RFC’s fortunes, the ‘Bloody April’ of 1917.

It is not too late to acknowledge the important role of the 42nd Division with twelve first-line (original) TF battalions from the Lancashire Fusiliers, the East Lancashire Regiment and the Manchester Regiment, together with the East Lancashire gunners from Blackburn, Church, Burnley, Manchester and Bolton (home of the fine memorial to the Bolton Artillery with nearly 200 Great War names, refurbished in 2016). Accompanying them were the divisional engineers, based in Old Trafford and the three East Lancashire Field Ambulances (Bolton. Manchester, Burnley and Bury). They took part in the significant action at Romani, in the Sinai Desert east of Suez, in August 1916 when the Lancashire Fusilier Brigade and the Manchester Brigade made their approach march in intense heat, wading through loose, soft sand under a fierce sun with little water. The Manchester battalions suffered particularly badly but with an interesting lesson in discipline:

In the depression between ridges there was not a breath of air … the sun grew more and more malignant … the men more dejected and taciturn. It was forbidden to drink from the meage ration of water unless by express order of an officer; the best outcomes where when this was rigidly enforced. But hundreds collapsed from heatstroke. An MO described the men as appearing to be ‘gradually suffocated …their faces turning a dusky blue’. (History of the 42nd East Lancashire Division)

Turkish forces were pushed back, suffering heavy losses, so allowing the building of the railway and water pipeline across the Sinai that would enable an eventual advance into Palestine. During the brutal and blistering approach march to Romani, the 42nd Division historian records that morale was maintained through unorthodox sources that today’s commanders still do well to recognise:

In this adversity the officers silently blessed [the soldier] whom they had so often found occasion to curse, ‘the funny man’ of the platoon or company. Luckily these men are to be found in every British unit, and when things are at their worst they extract humour from hardship [so] the most despondent feel less depressed. (Divisional History).

Either these men had signed on for 100 years or they occur, thankfully, in every generation and are with us today. The more chronic affliction was the transport, the camels, the vaunted ‘Ship of the Desert’. The Division’s historian wrote:

The volunteers who thought they could get any animal to answer to a pet name and turn soft eyes of devotion upon their master became prematurely aged and disillusioned men as they marched alongside a grunting, grumbling, snapping mass of vermin and vile odours whilst listening to its unpleasant internal remarks, gazing at its patchy hide and drooping snuffling lips. (Author’s note: he was referring to camels and not any member of the QM’s staff).

Territorials join the Royal Flying Corps for 1917’s ‘Bloody April’ and Beyond.

The 42nd Division sailed from Egypt for France in February 1917. There, as in other theatres of war, air power was increasingly important. At the highest level, Sir Douglas Haig had not forgotten the experience of losing on large scale pre-war army manoeuvres in England when movement of his divisions was identified by the RFC and in August 1914 Field Marshal Sir John French was warned in the encounter battle at Mons when the German encircling movement was spotted from the air. The RFC took less than 100 aircraft to France in 1914: by 1916, it had just over 400 and by the end of the war the RAF (born from the RFC and the Royal Naval Air Service in April 1918) had 4000 aircraft in all theatres. From simply a reconnaissance tool, they had taken on the spotting of artillery targets in conjunction with infantry and artillery officers on the ground and in controlling and correcting that fire, increasingly by wireless. The RFC was also developing a ground support rôle and eventually a strategic bombing rôle.

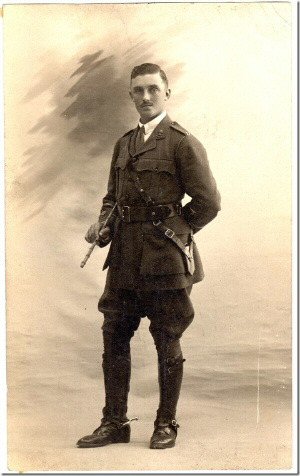

CROP.jpg) Some of the Territorials who went to the RFC did not stay long with their original TF units. The 22 year-old who was destined to become Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh Mallory left his father’s Birkenhead vicarage in the first week of the war and, whilst his father thought he was playing tennis, he was enlisting in the Liverpool Scottish. Distinguished academically, he served only eight weeks or so before being commissioned into the Lancashire Fusiliers, serving and being wounded in France and later transferring to the RFC in January 1916. Awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in January 1919, he joined the RAF with a permanent commission. His somewhat controversial WW2 career included commanding one of the Battle of Britain fighter wings and, in 1944, the entire Allied Expeditionary Air Force for D Day landings. He was killed in November 1944, flying over France (as a passenger) in bad weather to take command of Air Forces in the Far East. His brother, George, died on Mount Everest in 1924 in the famous ascent which may or may not have reached the summit.

Some of the Territorials who went to the RFC did not stay long with their original TF units. The 22 year-old who was destined to become Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh Mallory left his father’s Birkenhead vicarage in the first week of the war and, whilst his father thought he was playing tennis, he was enlisting in the Liverpool Scottish. Distinguished academically, he served only eight weeks or so before being commissioned into the Lancashire Fusiliers, serving and being wounded in France and later transferring to the RFC in January 1916. Awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in January 1919, he joined the RAF with a permanent commission. His somewhat controversial WW2 career included commanding one of the Battle of Britain fighter wings and, in 1944, the entire Allied Expeditionary Air Force for D Day landings. He was killed in November 1944, flying over France (as a passenger) in bad weather to take command of Air Forces in the Far East. His brother, George, died on Mount Everest in 1924 in the famous ascent which may or may not have reached the summit.

At the other end of the spectrum are those whose involvement was more ordinary. Rifleman William Fishwick, aged 47 and married with five surviving children, came from Birkenhead man. He was a second-line Territorial Force with 2/5th Bn., The King’s Liverpool Regiment, on home defence duties in Kent but with previous service with the 1st Lancashire Artillery Volunteers and the Caernarvon [now Caernarfon] Artillery Volunteers. On 27 December 1915, whilst guarding a wooden aircraft hangar at the then important Joyce Green aerodrome near Dartford at the height of a gale, the structure simply collapsed on him. He was found dead under an estimated 10 tons of debris with no obvious injury and was judged to have died of shock. His peacetime wage would have been between £1.50 and £2 a week; his widow got a weekly pension of £1.13 to support her and four children.

Variability of instructors and unsuitability of some training aircraft in the UK meant that for much of the war, pilot losses in training were greater than those in action until late in the war. Pilots were supposed to have had at least 15 hours solo flying before joining a squadron: they often arrived with less. Their active service was often shorter than their training particularly as British machines were generally technically inferior those of Germany until late 1917.This became a self-perpetuating cycle. With vacancies to be filled, pilots were increasingly rushed through training.

Variability of instructors and unsuitability of some training aircraft in the UK meant that for much of the war, pilot losses in training were greater than those in action until late in the war. Pilots were supposed to have had at least 15 hours solo flying before joining a squadron: they often arrived with less. Their active service was often shorter than their training particularly as British machines were generally technically inferior those of Germany until late 1917.This became a self-perpetuating cycle. With vacancies to be filled, pilots were increasingly rushed through training.

The policy of ‘no parachutes’ cannot have helped: they were seen to weaken fighting spirit and resolve although there were real issues of extra weight. Later, better training under a new ‘Gosport’ scheme lasting eleven months and the introduction of better aircraft, turned the tide against the German Luftstreitkräfte. However, in particular, April 1917 was the low point of the RFC’s fortunes. It became known as ‘Bloody April’ when twice as many aircraft (over 500) were lost in a month than in the whole five month Somme campaign in 1916. Major-General Hugh Trenchard, commanding the RFC in France and Flanders, pushed for maximum support for the BEF’s operations around Arras by pushing his aircraft out into German territory to ensure the supply of intelligence. His policy was aggressive even by the standards of the day. The out-numbered but technically superior Germans flew over their own territory, unhindered by anti-aircraft fire from either artillery or infantry, and with longer flying times. The German downed aircraft and surviving pilots were not lost. The enemy took full advantage.

2Lt Andrew Ormerod of Burnley, was an RFC casualty of the ‘Bloody April’ of 1917. He came from an ordinary background. The 1901 Census shows him as a 12 year-old ‘cotton worker’ - one of over 900,000 British children between 10 and 15 then at work. He joined the Royal Artillery Territorials (East Lancashire Division) and made his way up to sergeant-major and then a commission. The Burnley Express (December 1915) reported:

2Lt Andrew Ormerod of Burnley, was an RFC casualty of the ‘Bloody April’ of 1917. He came from an ordinary background. The 1901 Census shows him as a 12 year-old ‘cotton worker’ - one of over 900,000 British children between 10 and 15 then at work. He joined the Royal Artillery Territorials (East Lancashire Division) and made his way up to sergeant-major and then a commission. The Burnley Express (December 1915) reported:

Artillery Man’s Splendid Rise: Sergeant-Major Andrew Ormerod, … 1/1st East Lancashire Brigade RFA (TF) has been awarded his commission in the Artillery … well known and liked in the Burnley Lane district …rising in the Burnley Battery to become the youngest sergeant-major in the TF. … For a time Ormerod was attached to … the 130th (Howitzer) Battery and [at some time] he was in the fighting with [against] the Turks at El Kantara."

After serving in Salonika with the artillery, he transferred to the RFC. On the morning of 13 April 1917 he was flying as an observer in one of six RE8 aircraft (known as ‘Harry Tates’) of 59 Squadron RFC over German lines near Douai in France on reconnaissance. Within a matter of minutes all six were shot out of the sky when they encountered Jasta 11 (a German fighter squadron), led by Captain Manfred von Richthofen, known as the ‘Red Baron’ from the colour of his aircraft and who, before his death in April 1918, claimed 80 victories. On this occasion, one of the RE8s (although not Ormerod’s) became Richthofen’s 41st victory. Apart from the superiority of German aircraft and training at this time, the planned ‘top cover’ for the RE8s had failed to materialize. (Sources include the Ormerod family).

Lt Gabriel Coury VC had won the Victoria Cross before joining the RFC, At Guillemont in August 1916 he brought in wounded under very heavy fire and rallied troops under very heavy pressure. He had been at school at Stonyhurst College in north Lancashire where he served four years in the OTC) and was then apprenticed in Liverpool’s cotton trade. He was commissioned into 1st/4th Bn. of the South Lancashire Regiment TF, the pioneer battalion of the 55th (West Lancashire) Division. The end of his flying career illustrates the short-comings of training. Towards the end of 1916, Coury transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, flying initially on operations as an Observer in BE-2 reconnaissance aircraft. He returned to operational flying over the Western Front in March 1917, where his incredible luck continued flying in the highly vulnerable BE-2 aircraft but he survived “Bloody April” 1917. It was his last contact with the enemy in World War I. A month later he was back in Britain to re-train as a pilot. However, two serious crashes ended his flying career and he ended the war in the administration branch of the Royal Air Force. He returned to service in the Second World War, landing in France in 1944 in an anti-aircraft rôle and finishing the war with the rank of major. (Lancashire Infantry Museum).

Lt Gabriel Coury VC had won the Victoria Cross before joining the RFC, At Guillemont in August 1916 he brought in wounded under very heavy fire and rallied troops under very heavy pressure. He had been at school at Stonyhurst College in north Lancashire where he served four years in the OTC) and was then apprenticed in Liverpool’s cotton trade. He was commissioned into 1st/4th Bn. of the South Lancashire Regiment TF, the pioneer battalion of the 55th (West Lancashire) Division. The end of his flying career illustrates the short-comings of training. Towards the end of 1916, Coury transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, flying initially on operations as an Observer in BE-2 reconnaissance aircraft. He returned to operational flying over the Western Front in March 1917, where his incredible luck continued flying in the highly vulnerable BE-2 aircraft but he survived “Bloody April” 1917. It was his last contact with the enemy in World War I. A month later he was back in Britain to re-train as a pilot. However, two serious crashes ended his flying career and he ended the war in the administration branch of the Royal Air Force. He returned to service in the Second World War, landing in France in 1944 in an anti-aircraft rôle and finishing the war with the rank of major. (Lancashire Infantry Museum).

2Lt Walter Kember of Birkdale in Southport, was a casualty ‘under the guns of the Red Baron’. His name is on Liverpool University’s War Memorial. Originally enlisting as a Territorial at Southport in August 1914 in his early twenties, he crossed to France as No. 2415 in 1st/7th Bn., The King’s (Liverpool Regiment) TF on 7 March 1915 and was wounded in the leg during the battalion’s charge at Festubert in May 1915. After recovering he was commissioned into the 7th Bn. Lancashire Fusiliers (again TF) and then transferred to the RFC, flying with No. 6 Squadron.

On 1st September 1917 near Zonnebeke in the Ypres Salient, Richthofen, flying a Fokker tri-plane unfamiliar to the RFC, used only 20 rounds from a distance of 50 metres to account for the RE8 flown by Lt John Madge and Walter Kember. Richthofen’s report apparently said that the observer (Kember) made no attempt to fire back at him and was standing upright in the rear cockpit. This victory caused Richthofen to order his 60th silver ‘Victory Cup’: although he would run to over 80 victories, this was the last that he ordered. Madge survived, wounded and a PoW, and Kember was buried well behind the enemy lines although the grave was moved after the war to the Harlebeke New British Cemetery.

Captain Eric Gilbert Leake went to Sedbergh School, worked as a bank clerk and then emigrated to Canada. On the outbreak of war he joined the Canadian army, arriving in France in February 1915 to be wounded two months later. Having become a Company Quartermaster Sergeant, he transferred to a commission in the 7th Bn., The Manchester Regiment TF and then qualified as a pilot in January 1917, formally transferring to the RFC in March. In April 1917, in an RE8 during ‘Bloody April’, he had a lucky escape when his aircraft was damaged but the three others with him were shot down. Twice slightly wounded by anti-aircraft fire and shot down in March 1918 (when he and his observer walked away unharmed), he was awarded the Military Cross for action between 1 and 8 April 1918.

“On one occasion, observing a hostile scout, [Leake] at once attacked and fired 1000 rounds at close range. The hostile machine went down in a steep glide and crashed to earth. Later, when on contact patrol, his machine was damaged and forced to land just behind our lines. Although under heavy shell fire he, assisted by another officer, succeeded in saving all the instruments and equipment on the machine before destroying it. He set a very high example of courage and devotion to duty throughout the operations.” (GM 1914: The First World War in Greater Manchester).

The day after returning from leave [24 July 1918] he was wounded by heavy AA fire. Despite hopes for his recovery, he died in hospital on 31 July.

William Fitton, a scholarship boy from a humble background on the Wirral, joined the Liverpool Scottish on the same day as Percy Douglas in August 1914, going to France in November 1914. A signaller, he survived the battalion’s charge at Hooge in 1915 and was later awarded the Military Medal and promoted sergeant. Commissioned into the Lancashire Fusiliers in 1917 and married in March 1918, he transferred to the RFC, gained his pilot’s wings and went to France to join his squadron. . The Liverpool Scroll of Fame tells the unfortunate end to the story:

William Fitton, a scholarship boy from a humble background on the Wirral, joined the Liverpool Scottish on the same day as Percy Douglas in August 1914, going to France in November 1914. A signaller, he survived the battalion’s charge at Hooge in 1915 and was later awarded the Military Medal and promoted sergeant. Commissioned into the Lancashire Fusiliers in 1917 and married in March 1918, he transferred to the RFC, gained his pilot’s wings and went to France to join his squadron. . The Liverpool Scroll of Fame tells the unfortunate end to the story:

The very next day [19 August 1918] after reporting for duty he met with a fatal accident, for his machine got into a spin and "crashed" before he could right it, as it was only two hundred feet up. Thus a young life, he was only twenty-four, was cut off on the brink of another period full of promise of brilliant service, for, in the words of his squadron commander, "With such a fine record behind him we expected him to be one of our stars.”

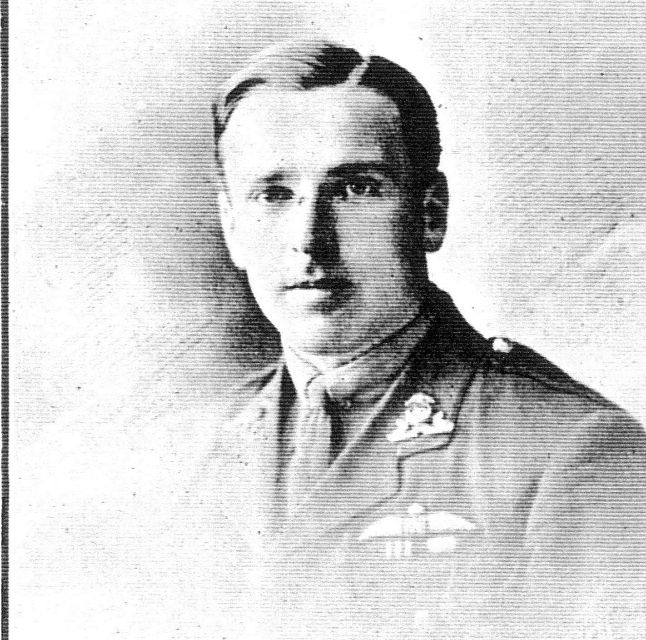

Lt Percy Douglas: Many machines carried not only the pilot but also an observer to operate cameras and wireless and man some of the various types of machine guns: there were various combinations of Vickers guns and Lewis guns. One of these observers was Lieutenant Percy Douglas who started his war as a Territorial by joining the Liverpool Scottish on the day after the war started. Was in France by November 1914 at the age of 17. Wounded near Ypres in May 1915, he was then commissioned into the Army Service Corps in July. He was wounded again in August 1916 and transferred to the RFC in August 1917 joining 11 Squadron. On a single morning on12th March 1918, his machine guns claimed five enemy scouts (fighters) seen to go out of control and another two aircraft two days later. Unsurprisingly this won him a posting to the School of Air Gunnery, a development in the improved training of aircrew.

It is worth saying that it has struck me in writing this that the RFC took its pilots and observers from a very broad range of society. Certainly there were men who could afford to fly before the war or were public schoolboys but equally there were those whose fathers (then ‘father’s occupation’ was a social reference point) were farm workers and mill hands. The criteria seemed to be solely bravery, aptitude, intelligence and determination, a tradition which the Royal Air Force has maintained for nearly 100 years.

Acknowledgements:

Paul Ormerod and David Ormerod Baxter, Jane Davies and Roger Goodwin (Lancashire Infantry Museum), Joe Devereux and Dennis Reeves, Messrs Dix Noonan Webb, the UK Defence Academy (M.O.D.), the New Zealand War Memorial Museum (Auckland, N.Z.)

Further reading:

The Lancashire Infantry Museum www.lancashireinfantrymuseum.org.uk

The Long, Long Trail www.longlongtrail.co.uk (Chris Baker)

The 42nd (East Lancashire) Division by Frederick Gibbon

The Birth of the Royal Air Force by Ian Philpott

Under The Guns of the Red Baron by Norman Franks, Hal Giblin and Nigel McCreery

Previous page: Come on the Lions: Another Bitter Winter

Next page: Mud Waist Deep, Rain in Buckets, the Start of ‘Third Ypres’