Training for the Great War

Pre War Training

The Territorial Force's training immediately before the Great War would be largely recognised by today’s Reservist, evening drills, weekend camps, musketry test, annual camp and other specialist courses. Orders appeared in newspapers and went by post, sometimes in magazine form including recent lectures. ‘Principles of Billeting’ might not greatly fire military ardour but there were articles on tactics and military history together with timeless comments on ‘disappointing attendance’ and ‘expecting a good turn-out for the General’ as well as details of extensive social and sporting programmes.

The infantry recruit did 40 one-hour drills in his first year and then 20 annually once ‘trained’. Musketry was very important but once the 90 rounds annual allocation was fired, any extra had to be purchased. Liverpool Territorials could travel to Altcar after work, shoot in the evening, eat and stay overnight in their unit hut (some of which still stand on the range), taking the train back to work next morning.

Weekend camps were less frequent than today: there was difficulty in financing travel. As Saturday morning working was normal Saturday afternoon training was common. Whether a machine gun course for sergeants, a tactical exercise for senior ranks on 'wild' Wirral heathland or recruit range afternoons at Altcar, Territorials worked towards the same professional skills as the Regular Army.

Annual camp lasted either 8 or 15 days: men could be fined in court for non-attendance. Fewer holidays made shorter ‘camps’ quite common but ‘second-week’ attendance measured a unit's efficiency and was rewarded with a £1 bounty (perhaps 60% of a weekly wage). Seaside camps were very popular so naturally the War Office tried to limit them to one in three. Usually brigade or divisional camps were organized but occasionally units ‘did their own thing’; the Liverpool Scottish battalion marched through Scotland in 1912. Camping grounds and training areas would often be rented and a divisional camp meant a lot to the local economy.

The Last Camp

In the late summer of 1914 amongst the gathering war clouds the battalion embarked on 2nd August for its annual camp as normal. The following diary entries,taken from the Trusts collection, show how those fateful august days were seen by some of those destined for the trenches of Flanders.

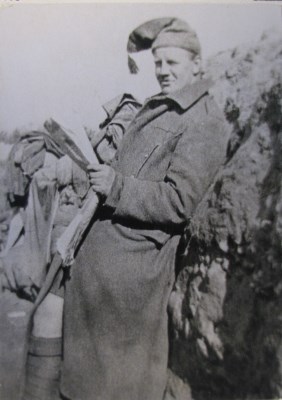

Lance-Sergeant David Marples of the Liverpool Scottish was in his mid-twenties when war broke out. Schooled at Calday Grange Grammar in the Wirral, he joined the Liverpool Scottish in 1910. His diary is unclear about his civilian job, possibly the Customs and Excise, but during every wartime visit to Liverpool, he loyally called at ‘the office’. Promoted full sergeant after mobilisation, he became a Company Sergeant Major in 1915. War took him to early fighting from November 1914, temporary return to civilian life on ‘termination of engagement’ in 1916 and then, persuaded to re-join, to a training role. Refusing a commission but returning to the Front in early 1917, he won the Military Cross at Ypres as a warrant officer, a rare occurrence, as well as acting as RSM for some time. He repelled a counter-attack one morning and submitted his marriage application later that day. He is similarly matter-of-fact about the outbreak of war.

Lance-Sergeant David Marples of the Liverpool Scottish was in his mid-twenties when war broke out. Schooled at Calday Grange Grammar in the Wirral, he joined the Liverpool Scottish in 1910. His diary is unclear about his civilian job, possibly the Customs and Excise, but during every wartime visit to Liverpool, he loyally called at ‘the office’. Promoted full sergeant after mobilisation, he became a Company Sergeant Major in 1915. War took him to early fighting from November 1914, temporary return to civilian life on ‘termination of engagement’ in 1916 and then, persuaded to re-join, to a training role. Refusing a commission but returning to the Front in early 1917, he won the Military Cross at Ypres as a warrant officer, a rare occurrence, as well as acting as RSM for some time. He repelled a counter-attack one morning and submitted his marriage application later that day. He is similarly matter-of-fact about the outbreak of war.

[2 August]:Left Lime Station 1:30 amidst great doubt as to … mobilisation. Arrived at Hornby Camp [Lancaster] at 5:30 pm … turned in at about 11:00 pm, amidst great rumours about the war and Germany's actions.

Expecting the unexpected …

[3 August]:Roused at 4:00 am with orders to strike camp, … entrained for Liverpool at 11:30 am … . Germany now at war with France, Belgium and Russia. Spent evening at [West Kirby], and gave an account of my shortest camp.

and going to work next day, clearly believing in ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ …

[4 August]:Resumed duties at the office, but nothing much doing owing to the excitement of the war. Spent evening [with friends]. British Army Territorials and Reserves ordered to mobilise for war.

Roughing it at the Stadium, the Theatre and the Adelphi

Reaction seemed rather livelier on 4 August for Lionel Ferguson, of the Liverpool Cotton Exchange, who was still charged ten shillings to offer his services to his country:

[4 August 1914]:… and I never shall forget that eventful evening [at New Brighton]: Everybody walked out on the streets to discuss the critical situation …. The Police were … delivering "call up" wires … and all that night one could listen to the knock of knockers around the small streets … at my office I found the cotton market in a panic, prices on the board jumping up pence a pound, but little … business to be done. Each City bank had a small rush for gold … In the afternoon I [went to] enlist in the Liverpool Scottish …. [passing] a queue of men over two miles long in the Haymarket …. At Fraser St. H.Q. things seemed hopeless … when I saw Rennison, [a Liverpool Scottish officer] and he invited me into the mess … getting me in front of hundreds of others. I paid my 10/- fee [50p], considered myself in luck to secure the last kilt which although very old and dirty, I carried it away to tog myself up in.

For the first few days, the Liverpool Scottish lived at home. On 7 August Ferguson collected a rifle and equipment which he casually stored at the Adelphi Hotel. This was clearly going to be a hard war:

[7 August 1914]: I reported … now a full Private in A Company… I was given a rifle, plate, bowl and sheet and told not to lose them. I deposited the lot at the manager's office in the Adelphi Hotel running into …Partridge [a friend] who insisted I should stop and have lunch with him and two other officers of the 5th Liverpool Regiment.

Lance-Sergeant Marples was also collecting his kit and his allowances

[7 August 1914]: Paraded at 10:00 am at H.Q. to draw ground sheets, entrenching tools and plates and basins. Received £5 mobilisation fee and 10/- [50p] for small kit and 6/- [30p] for 3 days' billeting.

By 8 August, the Scottish were hurriedly billeted in Liverpool. Sam Moulton, later groom for Captain Noel Chavasse VC and Bar, wrote:

[8 August 1914]: Orders were given to Tram Drivers and Police to tell Liverpool Scottish to parade at [HQ] at 10:00 p.m. – paraded - [six companies] occupied the Boxing Stadium in Pudsey St. and G and H Companies occupied the Shakespeare Theatre [opposite the HQ in Fraser Sreet.]. I … when Orderly Bugler, sometimes slept in Stadium and sometimes in the Shakespeare Theatre – of the two evils I preferred the Shakespeare. There I bedded down in one of the boxes and used the curtains as blankets, even so the night was often disturbed by some cheerful soul parading on stage wanting to sing and dance – in spite of the remarks that sprang up from various parts of the theatre. The Stadium was worse. There the gong that denoted the end of a round, seemed to have a fiendish attraction to all and sundry. Ball ammunition was issued to the Battalion (150 rounds per man).

On the same day, Marples moved into the comfortless Liverpool Boxing Stadium:

On the same day, Marples moved into the comfortless Liverpool Boxing Stadium:

[8 August 1914]: Paraded at H.Q. at 11:00 a.m. and marched off to the Stadium where the whole Battalion was quartered all day. Events very slow, and bully beef and biscuits for every meal. Has a great many boxing matches arranged. At 10:45 pm I was sent with an armed escort to arrest a deserter.

[9 August 1914]: Sunday, … Slept at Stadium and no blankets. Church Parade at 10:00 am…. Band selections afterwards and a concert in the evening.

There was a possibility that the battalion might be sent to Ireland to replace Regulars but it came to nothing. Except the 10% with an ‘Imperial Service’ obligation the Territorial Force was signed-up for home defence only however whole units, including the Liverpool Scottish, enthusiastically volunteered for overseas service.

Marples records:

[11 August]: The Battalion en masse offered its services to the War Office for any purpose whatever.

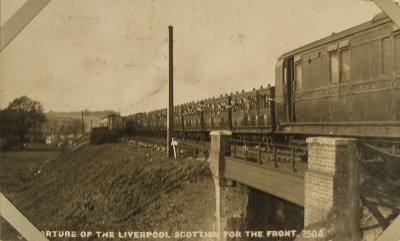

Eventually, on 18 August, the Liverpool Scottish entrained for Edinburgh with the rest of South Lancashire Brigade to form part of the Forth Defences. Within ten weeks, they would be on the muddy, wintery Flanders battlefield.

Previous page: The Territorial Force 1908-14

Next page: From Home Defence to the Suez Canal 1914